21 September 2024

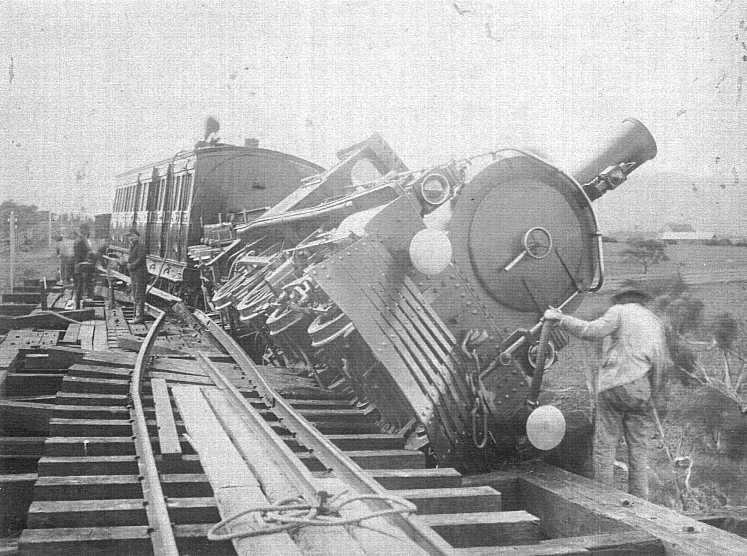

Photo: The Launceston ~ Hobart express, deliberately derailed on the Horseshoe Bridge, between Brighton and Bridgewater, Tasmania, 21 September 1893. Photographer unknown. Story below.

Playlist, Valley Sunrise Edition 800

0600 ~ 0900 AEST

| TRACK | RELEASE YEAR | TIME | PREVIOUS PLAYS | LAST PLAYED | ISRC |

| Frank Sinatra – The Song Is Ended But The Melody Lingers On | HOUR 1 | 0 | |||

| Gheorghe Zamfir – The Wind of Change | HOUR 1 | 1 | 10/1/2016 | ||

| Daniel O’Donnell – Everything Is Beautiful | HOUR 1 | 2 | 11/4/2021 | ||

| Jazz Kings – Still Got The Blues | 2023 | HOUR 1 | 0 | ||

| Terry Bennetts & Lee Forster – That’s The Kind Of Life I Live | 2024 | HOUR 1 | 3 | 26/7/2024 | |

| Ferrante & Teicher – Little Green Apples | HOUR 1 | 0 | |||

| Jason Carruthers – Coming Home Today | 2020 | HOUR 1 | 0 | ||

| Foster & Allen – Jim Reeves Medley | HOUR 1 | 1 | 30/4/2023 | ||

| 60 Year Diamond Classic – Charting on this day 1964 Tornados – Exodus | 1964 | HOUR 1 | 8 | 26/2/2021 | |

| 60 Year Diamond Classic – Charting on this day 1964 Eydie Gorme – I Want You To Meet My Baby | 1964 | HOUR 1 | 6 | 16/8/2015 | |

| Larissa Tormey & Remy O – Fire And Water | 2024 | HOUR 1 | 1 | 20/9/2024 | |

| Tony Clarke – Not That Kind Of Fool | 2024 | HOUR 2 | 2 | 13/9/2024 | QZ825 1857501 |

| David Paul Nowlin – Life Dealt Me This Hand | 2024 | HOUR 2 | 0 | QZWKY 2400220 | |

| Lon – Ride On | 2024 | HOUR 2 | 1 | 13/9/2024 | |

| By Request – Ella Fitzgerald – Someone To Watch Over Me | HOUR 2 | 0 | |||

| Francoise Hardy – Le Temps De L’Amour | HOUR 2 | 2 | 26/7/2015 | ||

| Brian May & ABC Melbourne Showband – Medley~Hello Young Lovers~Getting To Know You~I Whistle A Happy Tune | HOUR 2 | 1 | 2/8/2015 | ||

| Andrea Bocelli – Moon River | HOUR 2 | 1 | 18/7/2021 | ||

| Della Reese – Don’t You Know | HOUR 2 | 2 | 4/1/2019 | ||

| The Top 20 Billboard Tracks of 1962 No 15: Neil Sedaka – Breaking Up Is Hard To Do | 1962 | HOUR 2 | 2 | 10/9/2021 | |

| Jimmy Clanton – Venus In Blue Jeans | 1962 | HOUR 2 | 0 | ||

| Justin Jones – Country Roads | 2024 | HOUR 2 | 1 | 2/9/2018 | |

| Jade Hurley – Shake Rattle And Roll | HOUR 2 | 2 | 1/9/2023 | ||

| Billy McFarland – You’re So My Kind Of Perfect | 2024 | HOUR 3 | 1 | 6/9/2024 | |

| By Request – Paul Mauriat – Love Is Blue | 1968 | HOUR 3 | 12 | 3/11/2023 | |

| By Request – Belinda Carlisle – Summer Rain | HOUR 3 | 0 | |||

| By Request – Gerry & Pacemakers – Ferry Cross The Mersey | HOUR 3 | 18 | 15/9/2024 | ||

| By Request – Pussycat – My Broken Souvenirs | HOUR 3 | 1 | 8/9/2024 | ||

| Alan Caswell – A Friend To Me | HOUR 3 | 0 | AUGBT 2416828 | ||

| Eric Jupp & His Orchestra – Theme From Love Story | HOUR 3 | 1 | 14/3/2021 | ||

| By Request – Shavonne Aliphon – Always | HOUR 3 | 3 | 29/4/2022 | ||

| Matt Monro – I Love You Because | HOUR 3 | 0 | |||

| Johnnie Ray – Alexanders Ragtime Band | 1954 | HOUR 3 | 2 | 11/5/2018 | |

| Eddie Fisher – Lady of Spain | 1952 | HOUR 3 | 2 | 10/8/2018 |

COVER STORY

SABOTAGE ON THE HORSESHOE BRIDGE

It was the evening of Wednesday, September 20, 1893.

A strong westerly wind whistled through the tall, wooden pylons of the Horseshoe railway bridge, and across the undulating pasture lands near Brighton, 15 miles north of Hobart.

The shrill whistle of the evening express train, as it departed Brighton Junction station, and it’s rhythmic exhaust beat echoed, as it laboured up the gradient known as the Crooked Billet.

The train crew, Driver George Jones, Fireman Thomas Bagley, and Guard Henry Reynolds, and it’s 60 passengers had no idea of the danger ahead.

At twelve minutes past eight, the train mounted the summit of the Crooked Billet and entered a curve which led on to the Horseshoe Bridge. The train was now coasting comfortably along at 20 miles per hour.

Then, it happened. The locomotive suddenly left the rails, bouncing violently. It’s momentum and that of the coaches behind carried it along the sleepers of the bridge. Driver Jones and Guard Reynolds, who happened to look forward from his van at that very moment, immediately applied the vacuum brakes.

Just before it lurched to a stop, the locomotive heeled over to the left, coming to a rest at a 45 degree angle. Fireman Bagley would have plunged to near certain death but for a lucky grab for the exterior handrail of the locomotive. Dangling by one hand, he managed to reinforce his grip with the other and haul himself back to safety. He then carefully followed Driver Jones, who had climbed out the other side.

Guard Reynolds was crawling from sleeper to sleeper in the darkness, bracing himself against the wind which threatened to overbalance him. This bridge was the same as most wooden railway bridges of the time, in that it had no solid decking. There were sleepers, rails, supporting beams, and nothing else between.

Guard Reynolds called out, warning the passengers to stay aboard the train, because many of them would certainly fail to step securely along the sleepers in the dark and windy conditions, and plunge through the intervening void.

Driver Jones and Fireman Bagley examined their predicament. The left wheels of the locomotive were securely wedged between the ends of the sleepers and a stout wooden side-beam. It was only this, which prevented the entire train from being dashed to pieces in the gully below, with those on board.

The locomotive’s tender lay on its side, the coal, water, pannikins and firing tools it once contained having cascaded over the side. The two leading carriages were also derailed and canted over. The front end bulkhead of the first carriage had been shattered by the buffers of the tender.

Jones, Bagley and Reynolds carefully assisted their passengers from the carriages and guided them individually along the sleepers of the bridge to the safety of the southern abutment. This was no mean feat in the dark and windy conditions. The only casualties were two young men who were travelling in the first carriage, who had received cuts from a shattering gas lamp.

At the Hobart end of the bridge, and at intervals along the line, the crew found a collection of railway fishplates, stones, sleepers, and pieces of rail lying on the track. Examination of the permanent way at the Brighton end of the bridge revealed further interference. The stout fishplate bolts had been smashed, and the rails prised sideways with a ganger’s hammer, which lay nearby, its handle broken.

The chilling truth became apparent. This was not a chance accident, but a deliberate, calculated, and cold-blooded attempt to destroy the train, and all aboard!

[][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][]

The following morning, Sub-Inspector Marshall of the Brighton police found a soft brown felt hat with a red lining beneath the bridge. Seeing this as a potential clue, he found that a storekeeper in nearby Pontville, had a dozen hats like it in stock, of which two were sold.

One of these was still in the possession of its owner. The other was traced to a former railway employee, Charles Briggs, aged 27, who lived near Pontville. As he stated he had lost his hat the previous evening, his movements came under close scrutiny.

It appeared that on the morning of September 20, Briggs was wearing his hat when he visited the Bridgewater saleyards, where he purchased a cow, which he later lost.

Briggs had spent some time drinking in the Derwent Hotel, in Bridgewater, before leaving, partially intoxicated, at 6 p.m. with William Jackson, a local blacksmith. The men walked together along the main road until they arrived at a property known as Parkholme.

Without saying a word, Briggs suddenly left Jackson, crossed the road, climbed over the roadside fence, and ran towards the railway.

Knowing that a train was due shortly, Jackson was concerned for Briggs’ safety, and mentioned his concern to his wife upon his return home.

At 7 p.m. Douglas James and Alfred Wood were working in a stable on Wood’s farm, some 300 yards from the Horseshoe Bridge. Both men heard the metallic clanging of hammer blows, and assumed a team of gangers was working unusually late.

Briggs was not seen again until ten minutes to eight, when he entered the Enterprise Hotel, near the Brighton Junction railway station. He loudly remarked, that he had lost his hat, and stayed in the bar for some time.

The next day, news and rumours connected with the attempted mass-murder were raging, but Briggs was reticent to join any discussion, but preferred to concentrate on finding his missing cow.

Strangely, he denied seeing the derailed train whilst on his way to a site where he was employed on the construction of a new road although he could hardly have missed seeing it.

He seemed unusually anxious and nervous, but would not confide in anyone.

[][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][]

In Hobart, the Tasmanian Railways’ General Manager, Fred Back, took immediate steps to re-rail the train and restore the permanent way. Several teams of gangers were assigned to the extremely awkward task.

Tragedy struck late that day, when two gangers’ trolleys collided near Bridgewater. Most of the men were catapulted off and received minor injuries; but one unlucky fellow was seriously injured and died as he was being carried by train to hospital in Hobart.

Driver Jones, Fireman Bagley, and Guard Reynolds resumed their duties on Friday, September 22, taking charge of the afternoon express between Launceston and Brighton Junction.

The line between Brighton and Bridgewater was still not clear, so the express train terminated at Brighton Junction. It’s passengers and mail were exchanged for those carried by another train from Hobart to Bridgewater Junction station. The intervening distance was covered by road.

The gallantry of the train crew was later recognised when the Mayor of Launceston presented illuminated addresses to all three men on behalf of the Council.

By 10 a.m. on Saturday, September 23, the ill-fated train was back on the rails and had been towed back to Brighton Junction station.

[][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][]

That day, Superintendent Hedberg and Sub-Inspector Marshall interviewed Charles Briggs at his home. His replies to their intense questioning did not tally with the statements of other witnesses, so he was arrested and taken to the Pontville watch house.

Word of his arrest spread through the district like wildfire, and the Pontville Court room was crowded inside and out when he was formally charged the following Monday.

Briggs was remanded in custody and escorted back to the watch house.

The small Court building was again crowded when an inquiry into the derailment commenced on Monday, September 30. The evidence of 22 witnesses, from train crew, local hotel keepers, and residents was heard. At the end of these proceedings, Briggs was formally committed for trial at the next Hobart Criminal Court sittings, and again remanded in custody.

[][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][]

It was Tuesday, December 12, 1893, when Charles Briggs appeared before the Chief Justice and a jury. Briggs pleaded not guilty to two counts, that on the evening of September 20th last, he did unlawfully displace and move the rails and sleepers of, and place obstacles on the main line of railway at Horseshoe bridge, with intent to commit murder. The second count charged him with intent to endanger the safety of passengers travelling on the line.

Although 23 witnesses appeared for the Prosecution, doubts were cast by the Defence Counsel as to whether the hat found beneath the bridge actually belonged to Briggs. Was it lost by another person elsewhere, and/or did the strong wind which was blowing at the time happen to send it into the gully beneath the bridge? Briggs had claimed that he had lost his hat in the vicinity of the Jordan River. If that was so, it was never found.

But, then, what of the three men, one of whom was wearing white trousers, who were seen lurking near the bridge by several passengers immediately after the derailment, and who disappeared without saying a word?

Was it possible that a man under the influence of alcohol, as Briggs was when he left the Derwent Hotel in Bridgewater, could walk across the railway bridge without slipping between the sleepers, singlehandedly move rails weighing hundreds of pounds, then walk to the Enterprise Hotel in Brighton, all in 1 hour 45 minutes?

At 12.45 p.m. the jury retired to consider their verdict, which had to be unanimous in view of the capital charges involved.

By 10.15 p.m. the jury foreman advised the Court that there was not the slightest possibility of their arriving at such a verdict. The jury was then discharged, and Briggs was remanded again till the next sittings of the Supreme Criminal Court.

He languished in the Hobart Gaol over Christmas 1893, and it was Tuesday, February 27, 1894 when the second trial commenced. Over two days, this trial heard the same evidence, from the same witnesses.

After deliberating for 3½ hours the Court was advised that 10 jurymen were rigidly in favour of an acquittal, and 2 in favour of a conviction.

Charles Briggs was released from custody on Friday, March 2, 1894, to face an uncertain future, in view of the stigma now attached to his name and the high unemployment of the time.

So, the questions remain unresolved to this day __ did Briggs cause the Horseshoe bridge derailment, and attempt to murder over 60 people in cold blood? If so, what was his motive?

Or, was he an innocent victim of circumstances which resulted in months of wrongful, unjust imprisonment? Did the real culprit go free? What of the sinister sighting of the three men near the bridge by some of the passengers?

No one will ever know the truth.

22 SEPTEMBER IN HISTORY:

1951 Canberra, Australian Capital Territory – Following the Australian High Court’s ruling that the Communist Party Dissolution Bill 1950, passed by Federal Parliament to ban the Communist Party of Australia was unconstitutional, the Federal Government held a referendum on a proposal to alter the Australian Constitution to allow the banning of parties such as the Communist Party. The referendum was not carried.

1957 Eastern Atlantic Ocean – Four ships and an aircraft of the United States Air Force failed to find any trace of the 52 year old barque Pamir, which was believed to have sunk in a typhoon, south-west of the Azores.

Five survivors from the crew of 86 were subsequently rescued from a lifeboat.

1966 Near Winton, Queensland – 29 lives were lost when an Ansett ANA Viscount airliner bound from Mt Isa to Longreach crashed whilst attempting an emergency landing.

1993 Near Mobile, Alabama, U.S.A. – In the worst rail disaster in the U.S.A. since 1958, a group of heavy barges struck a railway bridge, displacing a span and buckling adjacent rails. Within ten minutes, Amtrak’s Sunset Limited passenger train, with 220 passengers and crew aboard, ran onto the displaced span, which then collapsed. The locomotives and several carriages plunged into the river, with the loss of 47 lives and injuring 103.